Thirty-three years ago, on the evening of 31st August 1975, I was out in my parent's back garden setting up my binocular tripod for a night of variable star observing. The sky was just beginning to get dark and the brighter stars were visible. As I was tightening various bolts on the tripod, I looked up and noticed a 2nd-magnitude star that shouldn't be there in the gap between Deneb and Cepheus. My first thought was that it must be a satellite, and I fully expected that, within a few seconds, it would have moved relative to the background stars. I looked down to concentrate on securing the bolts and then glanced up again. The star hadn't moved. I immediately realized it must be a nova.

This new star had actual been discovered by several observers in Japan two days earlier, on the 29th of August, when it was magnitude 3. Many other people around the world saw it on the the 30th when it had reached magnitude 1.8. Unfortunately I had been clouded out on that night, and by the time I saw it, it was already fading. The star was a distinct yellow colour when I first saw it, which suggested to me that it was already on the decline; novae are normally white or even bluish at or before maximum. Over the following weeks, the star became distinctly red as it faded.

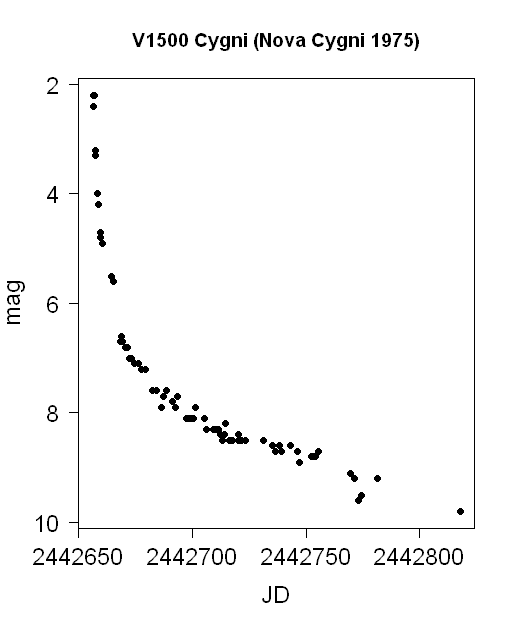

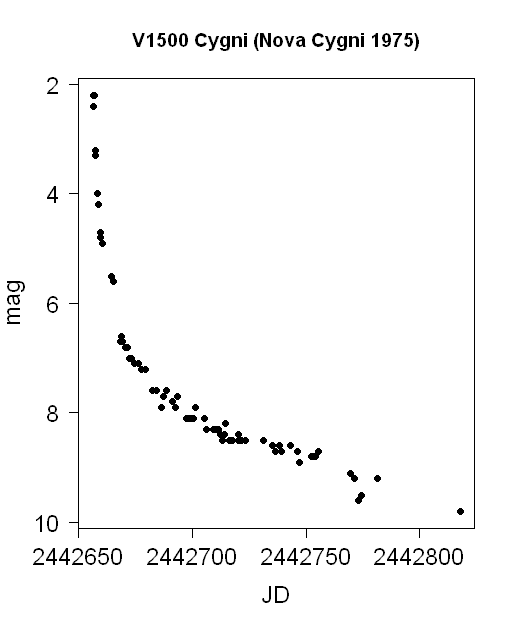

I continued to observe the nova whenever I could through to February of the following year. By then it had faded to magnitude 9.8. The above light-curve (a plot of magnitude against Julian Day number) shows my results. The very rapid early decline suggests that this was one of the most intrinsically luminous novae on record.

Fri 2010-10-22

Fri 2010-10-22