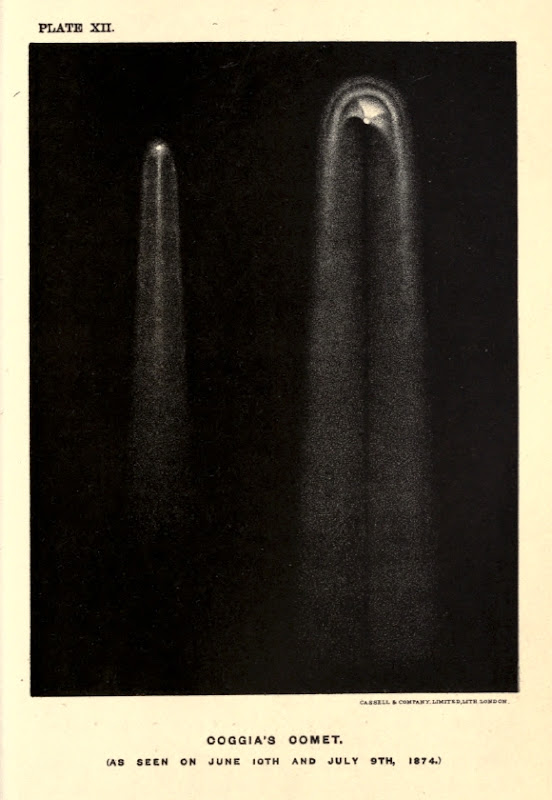

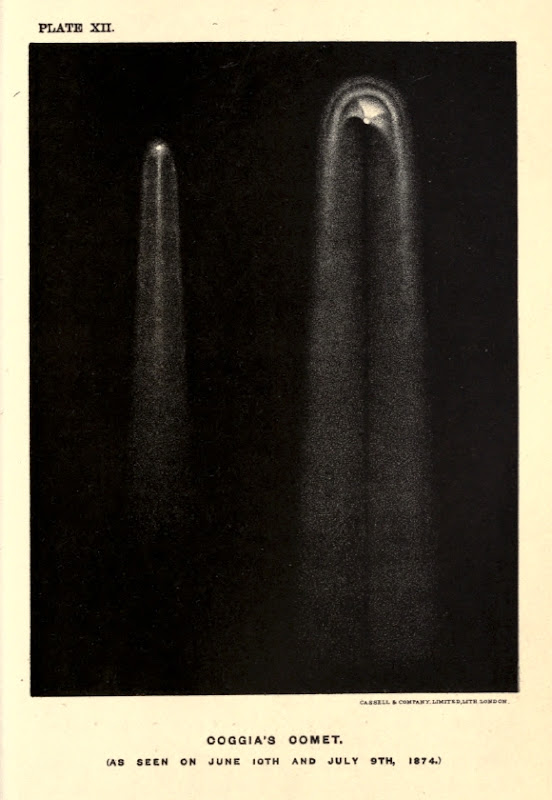

Another image from an old book, this time from The Story of the Heavens by Sir Robert Stawell Ball, 1893. Coggia's comet was studied spectroscopically by William Huggins, Father Secchi, Norman Lockyer and others. More details can be found here. It was also seen by the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins who made the following entry in his journal for 1874:

July 13. The comet - I have seen it at bedtime in the west, with head to the ground, white , a soft well-shaped tail, not big: I felt a certain awe and instress, a feeling of strangeness, flight (it hangs like a shuttlecock at the height, before it falls), and of threatening.

(Instress is a word Hopkins coined to mean the force or energy that sustains the inner nature of a person or object.)

Wed 2007-11-14

Wed 2007-11-14